Headline inflation is coming down fast now in the eurozone and the United States. It is however too early to consider the “monster” Christine Lagarde once referred to as fully caged. New research underlines the necessity of keeping that ”monster” under lock and key.

No champagne

The peak of inflation at around 10% is well behind us. In both the eurozone and the US headline inflation is now descending towards the 2% zone. But leave the champagne in the cooler for early next year inflation will rise again. This is due to what is labeled as “base effects”: the (very) low energy costs of the end of last year will start to count in the comparisons of annualized overall headline inflation rates. Moreover, some of the fiscal measures that were taken to reduce inflationary pressures will be phased out. In the meantime, core inflation, being headline inflation with energy and food prices taken out, only comes down very slowly and remains at around 5% in the eurozone and 4% in the US.

Oil, gas and wages

What happens next depends on several factors. First, will the highly combustible situation in the Middle East push up oil and gas prices once again? Second, what will happen on the wage front? There are some worrying signals flashing up from the labor markets, especially in the eurozone. The annualized growth rate of compensation per employee came out at 5.6% in the second quarter of 2023, 1.2 percentage points higher than the 2022 average. The dominant German trade union IG Metall is demanding a … 18% wage increase! They will not get such a wage rise, of course, but the demand as such is indicative of how labor relations and wage negotiations are evolving.

The third factor that will determine future inflation is the adopted monetary policy stance. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Federal Reserve (Fed) each jacked up policy interest rates spectacularly over the past 17 months and 21 months respectively. Although the time lag against which such policy actions work their way through the financial and economic system are still uncertain, it is rather evident that this tightening of monetary policy is contributing importantly to the observed reductions in headline and core inflation rates.

Expectations

In financial markets the idea that policy rates have reached their top is gaining traction, with major players even contemplating early rate cuts and hence envisaging a loosening of financial conditions. Belgium’s central banker Pierre Wunsch has, together with some of his colleagues, correctly argued that letting such expectations develop would be counterproductive at this stage of the fight against inflation. ECB president Christine Lagarde and Fed chairman Jay Powell have also been adamant that declaring victory over inflation would really be premature. Lagarde argued that the ECB “will need to remain attentive to the risks of persistent inflation” and that “our policy rates will be set at sufficiently restrictive levels for as long as necessary”. Powell went even one step further by pointing out that if growth did not slow sufficiently in the US and if labor markets remained tight, either “could warrant further tightening of monetary policy”.

Both Lagarde and Powell are clearly well aware of what has been extensively documented by researchers at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The researchers studied one hundred inflation shocks that transpired in advanced and emerging countries between 1970 and today. Among their observations is that “most unresolved inflation episodes involved ‘premature celebrations’” and that “countries that resolved inflation implemented restrictive policies more consistently over time”. Also highly significant is their conclusion that “countries that resolved inflation experienced lower growth in the short-term but not over the 5-year horizon”.

Neutrality in doubt

The discussion on the past and future path of monetary policy has reignited the discussion on money neutrality, i.e., the claim that changes in monetary policy mainly impact prices and have less of an effect on economic output and employment. The last conclusion from the IMF mentioned above is highly relevant in this regard. The extreme version of money neutrality is that even in the short run the effect of monetary policy changes is felt only on prices. The more accepted (though not generally accepted) version acknowledges short term effects of monetary policy changes on the real economy of growth, income and jobs but accepts the long-run effects to be almost entirely on prices.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco have developed new research that sheds important new light on the question of money neutrality (or not). Their elaborate empirical research on the topic covering the period 1900-2015 leads to two conclusions.

First, a tightening of monetary policy leads even in the longer run to a loss of growth (see chart 1). Accordingly, money neutrality even in its more moderate version does not seem to hold. The downward effect on GDP (Gross Domestic Product) comes entirely from productivity and capital formation effects, indicating that the venue through which the observed money-non-neutrality seems to be working itself out is investment.

CHART 1

Average responses to 1% unexpected increase in policy interest rate: 1900-2015

Secondly, there seems to be an asymmetric element in the way in which GDP reacts to monetary policy changes. Monetary tightening has, as pointed out, an important negative impact on the real economy (GDP) but the reverse does not hold (see chart 2). Monetary loosening leaves hardly a trace on the future path of GDP growth.

CHART 2

Real GDP response to unexpected policy rate changes

Further research on this intriguing topic is certainly needed but one policy conclusion to draw from what the economists of the Fed of San Francisco produced is obvious. Try to keep inflation under control at all times, because once you need to start fighting inflation, and that moment always comes when you let the beast out of the cage, there’s a considerable price to be paid in the sphere of the real economy, even in the longer run. The momentary conclusion should emphatically not be to walk away from the current tightening stance of monetary policy. That would indeed mean that the need to fight inflation will come back like a boomerang. The price to be paid then in terms of output, income and jobs will be higher than if central bankers at the ECB and the Fed hold the present line for a sufficiently long time.

Usefull links & downloads

You may also be interested in

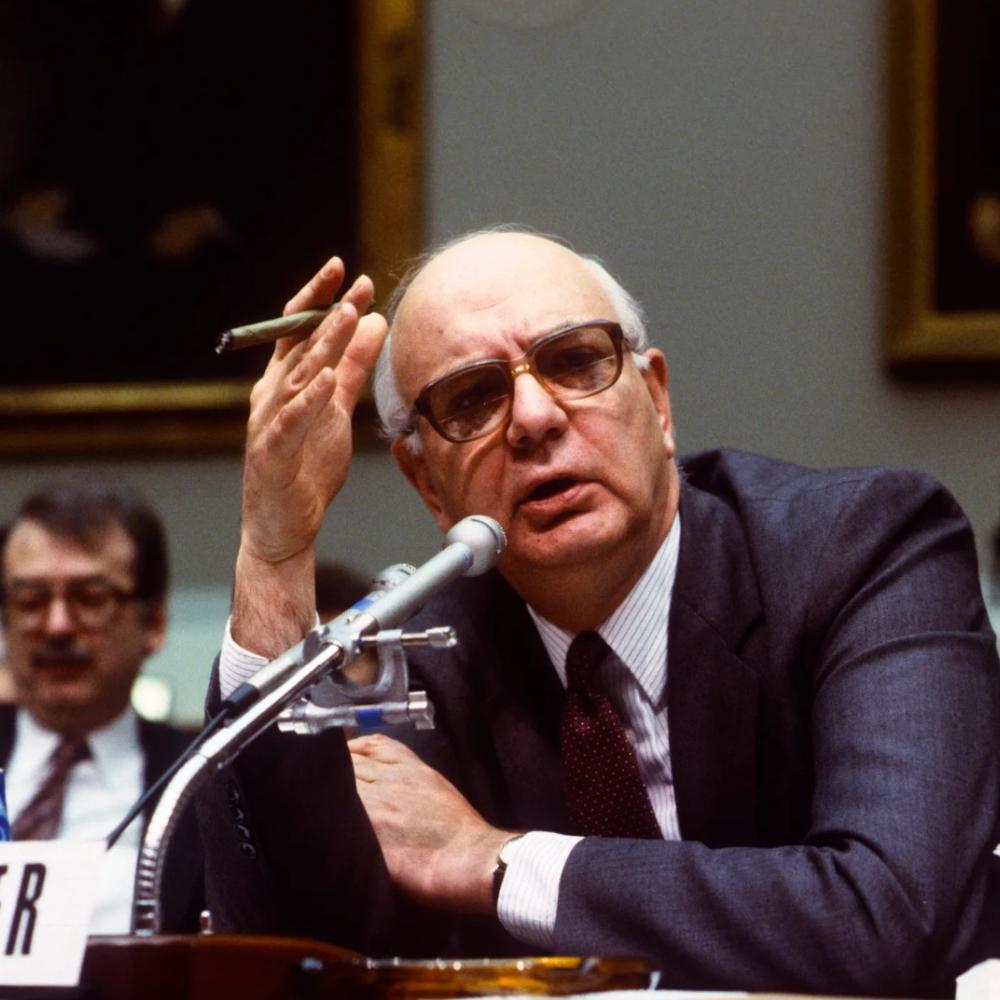

A Volcker Moment

The near-certitude of policy interest rate cuts by the Fed and the ECB in the near future is rapidly fading away. In the US more than in the eurozone the latest inflation data are worrying. A major lesson from history is that stepping back too early from a restrictive monetary policy is only asking for trouble further down the road.

The way to the Europe’s defense rehabilitation

The enthusiasm for a new EU Defense Fund should be tempered. Not only are there the problems and shortcomings that surfaced with the implementation of the EU’s most recent fund initiative, the Recovery and Resilience Facility, there is also a more fundamental issue that can no longer be ignored. This type of EU Fund creates enormous perverse incentives. Better alternatives are available.